Lieutenant Commander Dirk Hendrik Kolff (1761-1835)

Title of below article (free translation): Different memories of an exciting escape,

by Dirk Kolff, archivist (CBCA XVIIIn), translated to English by Marius Kolff (CBCD XVIIw4)

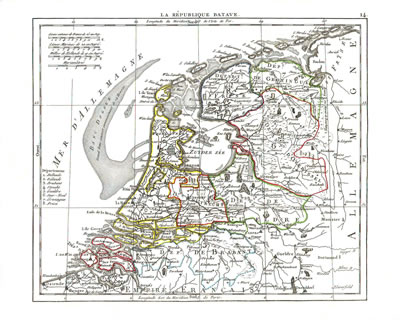

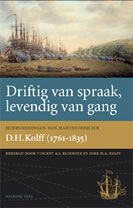

November 5, 2011, at The Hague (Muzee, Scheveningen) the first print of the biography of Dirk Hendrik Kolff (B XVIId) has been presented. The title of this biography is ‘Driftig van spraak, levendig van gang, herinneringen van marineofficier Dirk Hendrik Kolff (1761-1835)’. This publication, which is part 110 of the Werken van de Linschoten-Vereeniging, has been made possible by – amoungst others – the Kolff Family Association.

More on this issue (Dutch, new screen) >

To the Biography (History: Persons) >

Order this book (Association: Shop) >

| Below is the article as it appeared in De Colve XV (2010) on Kolff’s escape from imprisonment at The Hague (More on De Colve). |

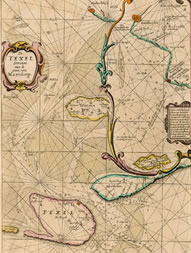

August 30, 1799, the navy squadron commanded by Rear-Admiral Samuel Story – eight ships of the line, amoungst which Story’s flag-ship, the ‘Washington’, three frigates and one brig – surrendered to the Brisith navy in the roadstead known as De Vlieter, northeast of the island of Wieringen. The Batavian flag was lowered. Under British command the ships sailed for England.

Commander of one the line ships, the ‘Utrecht’, was lieutenant-commander Dirk Hendrik Kolff (B XVIId) (1761-1835). Just like the other officers he didn’t have much of a choice. The crew as well as NCO’s who were siding with Prince Willem V, in exile in England, excited about the sight of all of the Orange flags they could see ashore because of a successful raid by the English at Kamperduin. The Batavian Republic seemed to be loosing out. Kolff had to admit – at the last court-martial on board of the ‘Washington’ – that, under these circumstances, also from the ‘Utrecht’ “no firing was to be expected” (note 2). Image left: Dirk Hendrik Kolff (Collection Kolff Family).

Commander of one the line ships, the ‘Utrecht’, was lieutenant-commander Dirk Hendrik Kolff (B XVIId) (1761-1835). Just like the other officers he didn’t have much of a choice. The crew as well as NCO’s who were siding with Prince Willem V, in exile in England, excited about the sight of all of the Orange flags they could see ashore because of a successful raid by the English at Kamperduin. The Batavian Republic seemed to be loosing out. Kolff had to admit – at the last court-martial on board of the ‘Washington’ – that, under these circumstances, also from the ‘Utrecht’ “no firing was to be expected” (note 2). Image left: Dirk Hendrik Kolff (Collection Kolff Family).

Afb. links: Dirk Hendrik Kolff (Familiebezit Kolff).

Image right: Samuel Story (Zaltbommel 1752 – Kleef 1811), painted 1811 by Howard Hodges (Scheepvaart Museum Amsterdam).

(Links to references at Wikipedia: : Vlieter Incident, Samuel Story) and [background information] on the Batavian Republic)

It had been the naval officer within him, the professional, who spoke as a member of the court-martial. No political choice was made here following his point of view. On the one hand there was, as he’d write in his biography “mijn oude bekende verkleeftheyd aan het Huijs van Nassauw” (my close attachment to the House of Nassau). On the other hand there was a resentment towards the English, that had taken away all of our colonies, against whom he had fought. Who, after their surrender, promised to retribute the officers for the loss of all provisions, which was personal property, but who never fulfilled this promise. “This promise was never realised: the English gouvernment never confirmed the evidence of their admiral and behaved to me, as so often before, never straight foward.” In any case, he had done what his duty obliged him to do. His point of view may characterise him as politically naive. For the Batavian gouvernment at The Hague it had been up to Kolff to choose between loyalty or treason to the newly 1795 erected national state. This, now, was the public morale.

Taken to their country by the British, he remained there not for long. He spoke about “onsen brave Stadhouder Willem de Vijfde” (our brave Stadtholder William V) and left soonest possible for the fatherland and to his family in Amersfoort.

Image: Waters between Texel and Noord Holland from P. Goos, ‘De Texel Stroom met de gaten vant Marsdiep’, 1666.

Click on the image for more information.

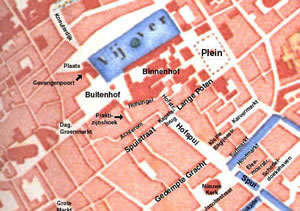

After having arrived there he was soon ordered by the ‘Agent of the Navy’ to notify them of his place of residence. He understood, of course, that this may have had something to do with the incident of the surrender of the squadron at the Vlieter. However, “convineced myself that in this situation there had been no other way of dealing”, he gave his address, even though this was generally known already. At the moment of his arrest he experienced difficulty to convince the Agent of the Navy that he was not a criminal but had to be treated as an officer following his right to that status. A coach was sent, with a certain leuitenant named Geweldiger, which was to take him to The Hague. There he was imprisoned in the so called ‘Hartogshuis’, the former palace of the duke of Brunswijk-Wolfenbüttel, later Ministry of Justice, in a street called Poten (Lange Poten). Eight months he had to spend there, a period which was an ordeal for him, and not only for him. Apart from what he, decades later, wrote about this himself, there is the more extensive narration dating 1898 (note 3) from one of his grandsons, whose main source was his mother, Kolffs eldest daughter Hanna. In the fate of her father, accused of high treason, she became to be a leading figure. In many points the stories of father and daughter are coincidal. Differences in tone, detail, and emotion, are noteable. They give extra depth to the story, also give more dimension to the story as we think we know it now. The difference between the story of the father, presented short and masculine, and the account of the daughter, showing a high degree of feminine perception is the lead of my article, even though I understand that not all can be explained this way.

Contrary to the masculine memories there are those of the grandson, more feminine memories depicting the despair of Kolffs spouse Margrieta. She travelled, being pregnant for four months, from Amersfoort to The Hague with Hanna. At The Hague she asks the authorities for permission to visit her husband. The sturdy Jacobin she talks to replies “nobody is allowed to visit prisoners of war” and, when she persists: “Madame, vous l’avez entendu.” Kolff didn’t know about this, also never wrote in his papers about his wife travelling in vain to The Hague. Locked up on the third floor of the Hartogshuis he remembers his room quite well. The lower windows were shielded of with wooden boards, the top ones were barred. However it was a spacious room, well equipped with good furniture. Two attendants served him. He was allowed to ask them for anything except for paper, ink, and books. Later the public prosecutor also allowed him this priviledge. One of the attendants, who seemed to be reliable, told the prosecutor about Kolff’s attempts to befriend him, and was awarded with a silver tobacco box. Kolff writes about this in a business like manner. Casually he writes about the three times he was interrogated, where he persisted in his previous report. The sounds of the bolts, which were used every day to lock him in, however, he found “rather unpleasant.”

Contrary to the masculine memories there are those of the grandson, more feminine memories depicting the despair of Kolffs spouse Margrieta. She travelled, being pregnant for four months, from Amersfoort to The Hague with Hanna. At The Hague she asks the authorities for permission to visit her husband. The sturdy Jacobin she talks to replies “nobody is allowed to visit prisoners of war” and, when she persists: “Madame, vous l’avez entendu.” Kolff didn’t know about this, also never wrote in his papers about his wife travelling in vain to The Hague. Locked up on the third floor of the Hartogshuis he remembers his room quite well. The lower windows were shielded of with wooden boards, the top ones were barred. However it was a spacious room, well equipped with good furniture. Two attendants served him. He was allowed to ask them for anything except for paper, ink, and books. Later the public prosecutor also allowed him this priviledge. One of the attendants, who seemed to be reliable, told the prosecutor about Kolff’s attempts to befriend him, and was awarded with a silver tobacco box. Kolff writes about this in a business like manner. Casually he writes about the three times he was interrogated, where he persisted in his previous report. The sounds of the bolts, which were used every day to lock him in, however, he found “rather unpleasant.”

Image: Map and view of Amersfoort, end 16th Century (Amorfortia Diocesis Ultraiectensis Oppidum amoenitate loci solique fertilitate admodum insigne, Braun & Hogenberg, 1588-97)

His death sentence was inevitable. Another shock brought him out of balance. On March 1, 1800, his wife Margrieta died, at Amersfoort, two weeks after the birth of a son – named Dirk Hendrik after his father. It was Scholten, his solicitor, who braught him this bad news. “I fell ill immediately”, he would recall later. Fortunately there was the possibility of blood-letting him and he gratefully recalls the name of the man who helped him with this. The recollactions by mouth of Hanna, as we think, is heavier. All sharp items had to be taken from the widower and “furiously he now demanded to see a member of his family.” This was allowed and so, eight days after the funeral of her mother, Hanna travelled to The Hague together with Martinus Kuytenbrouwer, who was married to her seven years older cousin Johanna Kolff. She was allowed to stay with this young couple at The Hague. Every evening from eight to ten she visited her father in the Hartogshuis. To him this was, according to his journal, “better than any possible medicine.” To which he immediately added “and by this I got connections outside of my room.” In other words: maybe now there an escape could be planned. The risk factor was very high, aspecially because Kuytenbrouwer was an officer in the artillerie in Batavian service, who was not supposed to have any clue.

Hanna could always visit without being searched first, as was the case with all other visitors. Her father doesn’t mention anything about this. The feminine version accounts of Hanna bringing him a good file: he used it to file through one of the bars with which he was almost finished when one of the maids betrayed him. There were more friends from the outside. One of them was Scholten, the sollicitor, who does not appear in Kolff’s account on his escape, but in that of Hanna he is the organizer of his second escape plan. In Kolff’s view his heroes are Hanna, and perhaps even more so, one of his two attendants: ‘a retired horse man’: Stepan Breijer is his name in the father’s memory, Lucas Bruiers in that of the daughter. If the escape would succeed he would get a guilder a day, for his life time – half of this amount for his wife in case widowed, adds the account of Hanna. The account of the father is sober, but also has gaps. He doesn’t tell that Breijer, who had been a tailor in his civil life, started to cut civilian clothing for his officer. The father also doesn’t mention that Hanna, following Scholten’s instructions, over a couple of days, smuggled in all of the material and smuggled out most of the important papers of her father, all under her own dress. None of the family members, where she stayed at The Hague, noticed any of this. Nor does he mention how Breijer, in the end, managed to create a well fitted black suit from all of the material.

Both accounts agree that tension rose, during these days in May, 1800. Kolff writes that Breijer told him about the death penalty of “the unfortunate and not-guilty ‘Capitijn’ Lieutenant Connio”, who had also been involved in the surrender of the escadre at the Vlieter and who had been imprisoned in a room above that of Kolff. He could hear how Connio was taken from his room to be shot to death. In Hanna’s account the apalling end of Connio got even worse: the officer would have preferred suicide over death on the scaffolding and after uttering “Fare well, Kolff”, cut his own throat with a razor knife. “His still warm blood drippled down through the wooden panels of the ceiling of Kolff’s room.”

As a soldier he remembered that, thanks to Breijer’s help, he got two good pistols with powder and lead as well as a ponjaard. That it had been Hanna who brought them these we have to learn from her. It was now two days before his execution. According to his daughter he pretended to be very ill and the mislead doctors prescribed several drugs, which Hanna got rid off silently. She was allowed to visit him more frequently, because these were to be his final days. The guards, who often got wine and food from their prisoner, may have lost count on who were in the room, because of the coming and going of people.

As a soldier he remembered that, thanks to Breijer’s help, he got two good pistols with powder and lead as well as a ponjaard. That it had been Hanna who brought them these we have to learn from her. It was now two days before his execution. According to his daughter he pretended to be very ill and the mislead doctors prescribed several drugs, which Hanna got rid off silently. She was allowed to visit him more frequently, because these were to be his final days. The guards, who often got wine and food from their prisoner, may have lost count on who were in the room, because of the coming and going of people.

In the city the Fair was at its height. In The Hague in May, when the Fair was on, no one stayed at home at night and it was rather chaotic in the streets. Even one of the guards seemed to have left for the Fair. Ten o’clock seemed to be the best time for an escape.

Inage: The Buitenhof at times of the Hague Fair, shown towards the direction of the Gevangenpoort, 1781. Click on the image for more information about the Hague Fair.

We note that how it was Scholten, in the daughters’ account, who prepared the escape from The Hague: a fourgon, a small carriage mainly for baggage, would be waiting near or at the Kalvermarkt. ‘Extra posting’ arrangements had been prepared all the weay right up to the German border, with at every station a ducate as tip for the fastest possible help in changing the horses. Damage to the carriage, or an injured horse, would be paid for instantly. The presumption was that “a noble man wanted to abduct his female”, not something an outsider wanted to get involved in. According to Kolff it had been himself who directed the entire operation. He urged Breijer to obey him without question and to not be ‘confused’, to which Breyer agreed. Kolff shivered when he noticed the obvious frightful feelings of this man. Hanna would, as usual say “Good night, papa, see you tomorrow” after which Breijer would take her to her cousins the couple Kuytenbrouwer. Breyer would close the door and shift the bolds, but not lock them. As usually he would then hand the keys to lieutenant Geweldiger in his room between that of Kolff and the staircase. This is how it went when we follow Kolff’s account. After Breijers departure he waited a while, and then went ‘very calm’, cane in his hand, silently passing the room of the lieutenant, who was seated reading, found the staircase and managed to open the front door, with some difficulty. On the inner court, outside, he walked right through the horse guards at the gate, but got held by a sergeant major, a German, who asked him about his identity. Kolff says: “My friend, don’t you recognize the doctor of the house?” upon which the man bowed. On the Poten he mingled in the crowd of the Fair and thus got to the Kalvermarkt. He found the fourgon, but not Breijer, whose life was in danger now as well, and who was supposed to accompany him. After 15 minutes Breijer showed up and they left for the direction of Woerden (direction Utrecht).

Image: Fourgon: searching the internet resulted in a lot of (new) vans; it is a small transport carriage for baggage.

At right top a fourgon from a Dutch website; below that one from a French website.

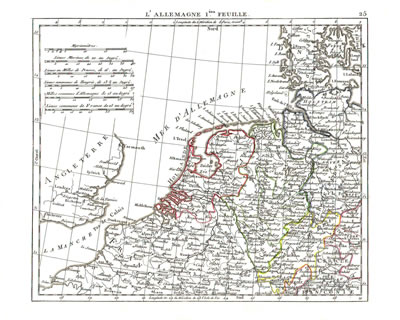

Image: The centre of The Hague with the names of the streets: Lange Poten/Plein, location of the Hartoghuis, the Kalvermarkt, where the fourgon was waiting for the escape.

Is this really how it went? The daughter has a different account. It had not been Breyer who’d brought her home. When her father had dressed up in the black suit, put on a whig, and placed a hat on his head deep down up to his eyes, he had left the room and she stayed behind alone in that room. These were her, as she declared, “the most frightful and painful moments in her already so turbulent life, for in every sound she heard she thought to hear her father being brought back.” After half an hour she called a servant and said she wanted to go home.

She had arranged her father’s nightcap carefully on the bed and hung father’s clothes on the side. While leaving the room she wished her father good recuperation and a good night, in a way that the guards could hear her. With trembling voice she told the lieutenant that her father was resting now, upon which the lieutenant ordered his own attendant to take Hanna home. Once there, she couldn’t say anything about the escape, she fainted, and only came around after repeated blood-lettings. The next morning Scholten visited her at the Kuytenbrouwers and gave her instructions. A carriage came to pick her up to take her for questioning. We have detailed information on her replies to the Council of War who questioned her. She never mentioned Scholten, which could have been fatal for him. She even interrupted in French when the gentlemen, behind the large table – covered with green linen, were deliberating. In the end the chairman’s heart seemed to have melted, he took her on his lapse, kissed her and gave her jams.

The father accounts of his journey by night via the outer city canals of Utrecht, not going through but around Arnhem, towards Huissen. Huissen was Cleve territory, which was then a part of Prussia. From there he wrote to the Agent of the Navy and asked for a fair trial. After a couple of days his request appeared to be in vain. He then travelled on to Oldenburg, where he had an acquaintance. He settled himself there. Half a year later Hanna came to live with him.

This how father and daughter each of them wrote what they could remember when they thought back of these occurances whenever the family asked them about it. These have been their personal recollections of what had touched them most in those exiting days.

Breijer remained at Oldenburg as well and got his annual allowance of 365 guilders until his death in 1805.

In 1814 Kolff’s death sentence was cancelled. He returned to his fatherland with his second wife. Hanna got married in Oldenburg, became a widow, married again. She died in 1829, six years before her father. All of her life the portrait that he got painted of himself, and which he presented her as a sign of gratitude, must have hung in her house. It was returned to him after her death. That painting and their accounts, is all we have of them. Surely we will find more in archives on Dirk Hendrik Kolff and maybe even also of his daughter Hanna. We are working on this. The question remains whether we will get to know them better than from their memories of springtime 1800 in The Hague, especially because they are so different, even contradictory.

This map shows Huisen (Huessen) is not a part of the Batavian Republic, but of Prussia.

| Dirk Kolff, archivist, website: Marius Kolff, May 2010 |

| Notes: numbers follow the original text (where numbers are not shown: notes 1, 4, 5: are references to links at this site, which have been added here and have become obsolete here): Noot 2: I quote, just as below in this article, from the hand written biography of D.H. Kolff. The Family Association expects to have these published soon in print. Noot 3: In the Leeskabinet of August 1898; later re-issued by the Family Association (still available). |